Mosquitoes: World's Deadliest Animal

Mosquitoes cause around 1 million deaths a year by transmitting diseases such as malaria and dengue. Find out why they are so deadly

04.12.2023

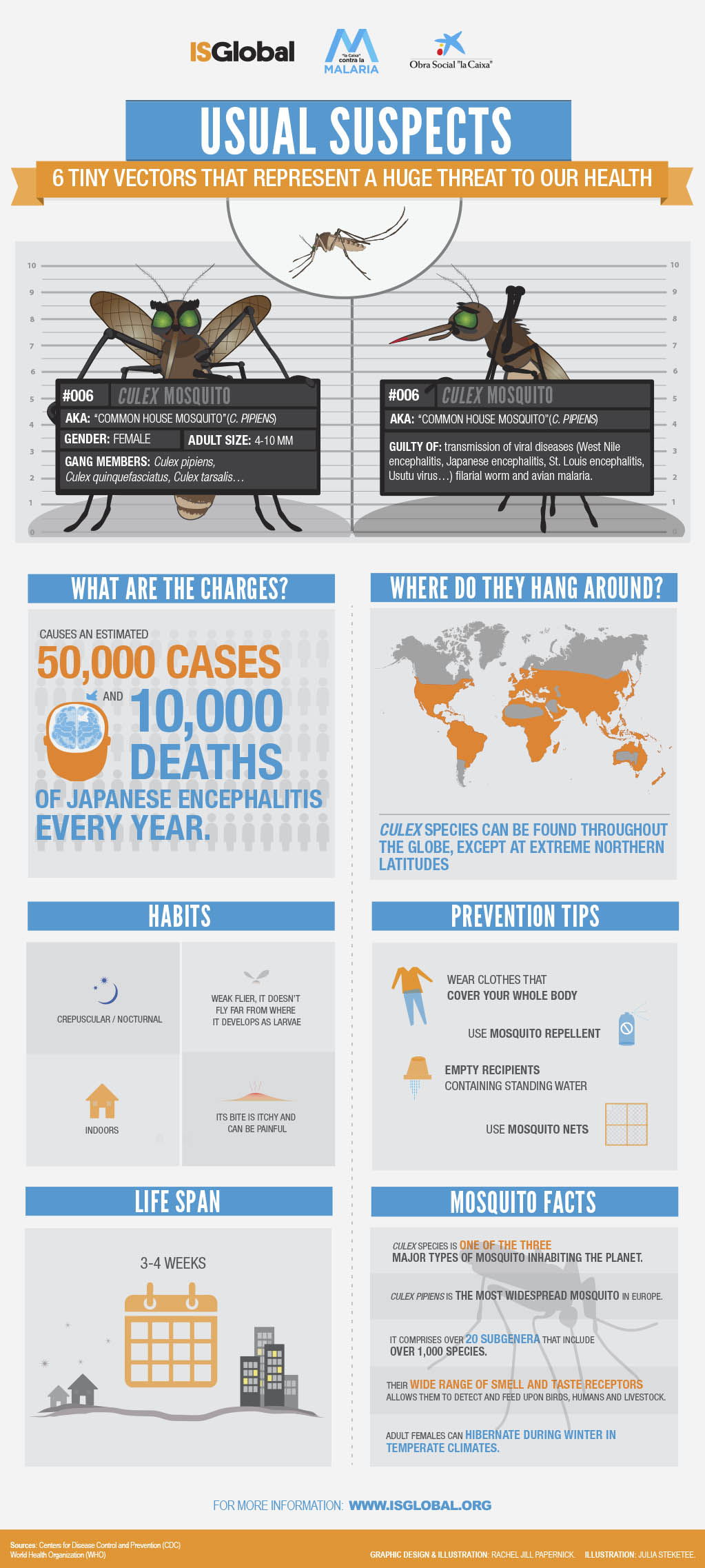

When we think of deadly animals, we tend to think of sharks or snakes. But the deadliest animal in the world, in terms of how many people it kills every year, is by far the mosquito. Although estimates vary, some sources believe that mosquitoes are responsible for up to 1 million human deaths per year, whereas snakes kill an estimated 100,000 and sharks a mere 10 (humans by the way are second behind the mosquito, causing 400,000 deaths every year).

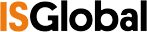

True, this tiny insect does not do the job on its own. What makes it so dangerous is its capacity to transmit viruses or other parasites that cause devastating diseases. Every year, malaria alone, transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito, kills 600,000 people (mainly children) and incapacitates another 200 million for days. Other mosquito-borne diseases include dengue, which causes 100 to 400 million cases per year worldwide, yellow fever, which has a high mortality rate, or Japanese encephalitis, which causes more than 10,000 deaths per year, mostly in Asia. Not to forget Zika virus, with its recently described devastating and long-term neurological effects in babies born to infected mothers.

How many mosquito species are there?

There are more than 2,500 species of mosquito, and they are found in every region of the world except Antartica. In fact, mosquitoes are very good at adapting to new environments and to any intervention we use against them. For example, Aedes aegypti (vector of yellow fever, zika, dengue among others) has adapted incredibly well to urban environments: it feeds only on humans and can lay eggs in a wide range of outdoors and indoors containers. Many mosquito species, including Anopheles, have evolved resistance against a variety of widely used insecticides and have changed their feeding habits (they now feed outside and earlier) so as to avoid bed nets and insecticide-sprayed homes. In recent years, ‘Anopheles stephensi,’ historically known as the Asian malaria vector, is rapidly spreading in Africa and posing great challenges to elimination efforts in the region. This invasive species transmits both Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax malaria and thrives in both rural and urban settings.

Approaches to fight mosquitoes

Mosquitoes are difficult creatures to deal with. They are constantly evolving and learning to evade the tools we use to fight them. In this ongoing battle against the relentless bloodsuckers, research at ISGlobal is providing hope for more effective mosquito control strategies.

ISGlobal has a long history of working on malaria research and currently hosts several groups including the ‘Malaria Immunology Group’, the ‘Malaria Epigenetics Lab’, the ‘Nanomalaria Group’, the ‘Plasmodium Glycobiology Lab’, ‘Plasmodium vivax and Exposome Research Group’, ‘Malaria Physiopathology and Genomics Group.’

Researchers also exploring new vector control strategies that can complement existing tools and help us overcome the worrying developments around insecticide resistance and residual transmission of malaria.

Mosquitoes are attracted to some people more than others

Ever felt like mosquitoes have a special preference for your blood? That could indeed be the case! Mosquitoes are often attracted to certain individuals more than others due to factors like body temperature and amount of carbon dioxide in exhaled breath. Pregnant women, in particular, seem to be a favourite target for mosquitoes, leading to numerous cases of severe dengue and malaria in pregnancy. To tackle the latter challenge that threatens the lives of both pregnant women and their children, researchers at ISGlobal are studying novel chemoprevention tools and exploring the best ways to improve the coverage of tools that prevent malaria in pregnancy.

Climate change and mosquitoes

Experts warn that earlier forecasts about the effects of climate change on mosquito populations are now manifesting as reality. Since 2000, dengue cases have skyrocketed, with an eight-fold increase. We can now see it rapidly expanding in Europe, the United States, and in new parts of Africa.

Climate change marked by significant changes in temperatures, drought and precipitation patterns can impact malaria control and elimination in complex ways. Though there needs to be further research on the direct impacts of climate change on malaria transmission, we are already witnessing the indirect impacts of extreme weather events like floods on malaria programs.

In early 2023, Cyclone Freddy, an exceptionally long-lived and destructive cyclone hit Mozambique twice, destroying infrastructure and leaving 198 people dead. Members of the ISGlobal-led BOHEMIA project, who were conducting a large malaria trial in the country were witness to the immediate impacts of this natural disaster on people’s health, evidenced by the peak in cholera and malaria cases following the cyclone.

In this context of converging biological, socio-political and environmental threats, it is more important than ever to support endemic countries increase surveillance for mosquito-borne diseases and ensure that the R&D pipeline for new tools to fight these diseases is well-replenished.